Why Publish?

Remember, humanities publication is always a conversation with past and contemporary scholars in your field of study.

Most graduate students have to take a writing course in their first year. The main purpose of such courses is to teach them the techniques about researching and writing  scholarly articles. Based in my own experiences of publishing academic articles and monographs, this brief guide is meant to augment what you might have learned in your classrooms. While I cannot promise absolute success, I do, however, suggest that some of the steps outlined in this guide could be quite useful for successful publishing in the humanities.

scholarly articles. Based in my own experiences of publishing academic articles and monographs, this brief guide is meant to augment what you might have learned in your classrooms. While I cannot promise absolute success, I do, however, suggest that some of the steps outlined in this guide could be quite useful for successful publishing in the humanities.

This guide is organized in four parts: Part One covers the philosophical and practical reasons for publishing, Part Two provides the details about research and writing of a scholarly paper, Part Three deals with writing the first draft, and Part Four informs you about the process of submitting your paper to the right journal and following it through to its ultimate publication.

Why We Write and Publish?

Though all of us in the humanities are trained and are expected to write and publish, we are never really encouraged to ask ourselves as to why do we need to write and publish? Answering this question is key to developing the kind of academic writing and research one conducts. Listed below are some of the reasons that I have heard about the need to write and publish:

- To produce knowledge.

- To contribute to our Field of Study.

- To impact the world.

- To meet professional requirements.

- For professional recognition.

- To create a body of work.

Writing to produce Knowledge

When we write to produce knowledge, what we are acknowledging, imperceptibly, is that we see ourselves as producers of knowledge in our field. The writing so guided, tends to rely on an Arnoldian model of research and encourages a sort of scholarship of detachment. The scholarship of detachment is deeply concerned with the objectivity of our work and is more focused on the long-term impact of our writing. Writers who are motivated by this mode of writing, often do not tend to be engaged with current politics or state of the world; their writing, thus, tends to hope to accomplish some change over a long period.

We often we also use this mode of thinking to rationalize our privileged location in the academy and through this market-derived understanding of our work, we can protect ourselves from the every-day wants and needs of the world. Thus, while the world continually moves toward harsh inequalities and brutalities of gender, race, and class we can keep writing our deeply specialized esoteric works thinking to ourselves that we are doing our share of work and in the end in the long run, when the world catches up with it, our work will become relevant and will be understood and be used to change the world.

Most social scientists rely on the same kind of argument. Since they are trained to think of themselves as scientists , they have to create an aura of detachment from their object of study. As a result, they train themselves to collect the data and then provide a dispassionate analysis of the data. This became clear to me after a conversation with a sociologist friend recently. When I asked him as to what his opinion was about how to change the living conditions of the group he was studying, his response was that seeking an amelioration of the situation of his sample subjects was not his job and if he did so, he would become an activist. His argument was hinged upon the belief in knowledge production and under this logic, his job was to produce knowledge for activists, governments, and other bodies. It was the function of those other groups to use his meticulously collected and analyzed data to make policy changes.

There is nothing wrong with thinking like this and if this is how you have been trained in your field then your research should be guided by this, but keep in mind that this is only one disciplinary approach and if you find essays that do not follow this pattern, then those essays might have been conceptualized and composed under a different set of assumptions.

Writing to Contribute to our Field of Study

In one of his books, one of my former colleagues, Mark Bracher, terms this the “discourse of the discipline.” Under this register, we teach our students the major debates in their fields of study in order for them to specialize. The students, in turn, worry only about the discipline and what is current and in vogue in it and then produce professional scholarship that displays their knowledge of the field. Needless to say, this knowledge of the field is necessary for professionalism and also for publications, for how would one come up with something new to publish if one did not know about the current debates of the field of study?

Naturally, if your writing is field-specific, knowing the filed, its major critics and theorists, and its established canon is a prerequisite for writing publishable articles.

Writing to Impact the World

While this is what guides most of my scholarship, this mode of approaching one’s research is still quite controversial in the English departments. By and large, most senior established scholars in most of the English departments feel that it is not their job to try to change the world. Mostly younger scholars or scholars who specialize in highly political or contestatory fields (gender studies, postcolonial studies, African-American studies etc) tend to do mostly political and activist work. Their writings, by and large, tend to connect the critical analysis with the world outside the academy and hope to either effect some change or at least have an ameliorative strain. If this register is important to you, your writing will have to be different from a traditional paper and will have to engage with the real world issues.

Writing to Meet Professional Requirements

This probably is the least heroic reason to write and publish, but has the most impact on your life as a humanities scholar. First , if you are a graduate student, you are pretty much required to write research papers for your graduate courses. Secondly, while in graduate school you are also required to produce a finished and defendable dissertation.

If you are a graduate student entering the job market, your faculty mentors will advise you to publish in your field, for only then you will be competitive with all the other freshly minted PhDs entering the market.

Furthermore, even after you land a tenure track job, you are required to produce a consistent body of work in order to keep your job, win tenure, and get professional promotions. Thus, even though this sounds like a very cynical reason to publish your work, this, in fact, happens to be the prime motivator for a lot of scholars to continue publishing.

To Garner Professional Recognition

Whichever sub-field of literary studies you are engaged in, one important reason to write and publish your work is also to garner material and symbolic recognition. If you become a well-known figure in your field of study, through your publications, not only would your institution acknowledge it in material terms but your opinions within your department and outside of it would carry more weight.

This recognition is not just self-serving: it is in fact connected to pretty much all that you want to do as a scholar. As a highly published scholar, you will be more mobile, attract better graduate students, be asked to give public presentations, and will generally be regarded as the person to go to when questions about your specific expertise arise in the media as well as in the academia. Having this symbolic recognition can, in turn, assist you personally but can also help you in placing your graduate students’ work, and, if you like, it can also help you make an impact in the world.

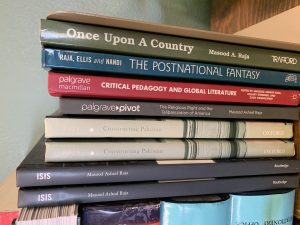

To Create a Body of Work as a Reference

This aspect of scholarly publishing became clear to me when I started writing political blogs and when the frequency of my public talks increased. In both instances when someone objected to my views in a blog or in a talk—considering the narrow focus of the topic—I started referring them to my other published work where, it seems, I had already answered that particular question. Thus, overall if as a scholar you also hope to have a public presence, you will realize that your body of work itself becomes a reference for you to argue your point to varied and diverse reading or listening audiences.

Conclusion

Overall, I have suggested in this article that we all have different reasons to want to publish our work, but there never is a single reason for it. It is important for you as an emerging scholar to know why you write, for this knowledge will guide your research and publication priorities. In the next article , I will discuss, albeit briefly, the research process involved in writing a publishable paper. But please do bear in mind that the reasons to write as discussed in this article will still play an important role in your research process, as your research priorities and methods will be guided by the underlying reasons to publish. (Continue to Part Two)

[…] Part 1 […]

[…] your notes, formulated your thesis and are ready to commit to writing a first draft (Please do read Part 1 and Part 2 of this series) . Bear in mind that the way you write is absolutely depends upon your […]

[…] Previous […]

This is the most needed and informative write up I’ve come across yet.