Academic Articles: Writing the First Draft

Needless to say, there are plenty of good books on writing academic articles, especially written by composition theorists and scholars, that can help you learn the art of crafting the first draft of your academic articles. This, essay, therefore, contains brief guidelines based in my own personal experience of writing the first draft, an experience that of course relies on the knowledge I gained during my education and in actual practice of writing publishable articles.By now, I am assuming, you have conducted your research, taken your notes, formulated your thesis and are ready to commit to writing a first draft (Please do read Part 1 and Part 2 of this series) . Bear in mind that the way you write is absolutely depends upon your own personal techniques of writing: some people, I for example, sit down and write a complete first draft in one sitting; some take their time and develop their draft paragraph by paragraph making sure to get the writing as perfect as possible to the final version. In my case, I have found a quick writing of the first draft more useful to the way my mind works.

Some Basic Steps to Drafting Academic Articles

My essays usually need more extensive editing after I have composed my first draft. So, please figure out what is your “natural” style and then follow its rhythms in writing your first draft. Here are some of the steps I follow:

- I make sure that I have sufficient time to at least finish the draft in one sitting.

- I work with a practiced structure (explained below) so that the ideas are generally transcribed in the sequence in which they are supposed to appear.

- I do not stop to add quotes/ citations in the first draft. Instead, I just leave myself hints to add it it later. For example, if discussing a certain idea by a theorist I would write “In his book X Foucault discusses the use of power as follows: YY). Or leave myself a note like this: “Insert quote from xxx.”

- The point is to capture and develop your own ideas and thoughts first. You already know what are you conceptually responding to, and the specifics of the “What” can be added later.

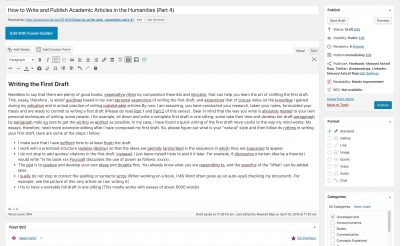

- I try to have a workable full draft in one sitting (This mostly works with essays of about 6000 words). I usually do not stop to correct the spelling or syntactic errors (When working on a book, MS Word often gives up on auto-spell checking my document). For example, see the errors in a picture of this very article as I am writing it:

Some Things to Keep in Mind

I am not going to belabor the mechanics of writing the draft, for I am assuming you already know that, but my purpose here is to share the process that works for my writing and might be of some use to you. Here are some of the things I keep in mind while composing my first draft:

Introduction and Thesis

In the beginning of my essay, I briefly introduce the text I am writing about. Usually, this introduction is one compact paragraph and includes the main thesis of my essay. For example:

PUBLISHED IN FRENCH in 1960, Ousmane Sembene’s Les bouts de bois de Dieu [God’s Bits of Wood] serves a two-pronged purpose of representing a narrativized, particularistic account of a strike while also offering certain universal aspects of class struggle. This dual focus on the local and the global makes the novel a perfect didactic instrument for teaching resistance in the current state of neoliberal capital. Using Fredric Jameson’s concept of the ‘ideologeme’, this essay discusses the novel’s attempt to represent the 1948 Dakar strike as a clue to learning the absolutely necessary preconditions for successful resistance in the neoliberal regime of high capital. 1

Explain your Theory and your Reasons for Writing the Essay

I make sure to cite and explain the particular theory that I am using. It is important to explain as to which particular “understanding” of a theory or a concept are you using, so that your readers know that you are applying a specific understanding of the theorist or theory. Furthermore, this brief explanation also kind of “teaches” the reader as to how to read your essay clearly. Here is an example of this practice:

The habitus is both the generative principle of objectively classifiable judgements and the system of classification (principium divisionis) of these practices. It is in the relationship between the two capacities which define the habitus, the capacity to produce classifiable practices and works, and the capacity to differentiate and appreciate these practices and products (taste), that the represented social world, i.e., the space of life- styles, is constituted. (Bourdieu 1984: 170)

To unpack this, a habitus both produces the system of judgements [of taste and art etc.) and also provides a classification, or hierarchy, of these judgements. For example, the distinction between high and low art would, in this sense, be constituted by the habitus and then explained and formulated within the same logic of the habitus. And, as Bourdieu suggests, it is within the gap between these two corresponding functions of the habitus that one can learn the governing system of appraisal within a specific lifestyle. This aspect of the habitus is important to bear in mind while dealing with PWE [Pakistani Writing in English] and its reception within and without Pakistan. 2

From one of my recently published book chapters, the above is an example of introducing your theory and then explaining its specific usage in your argument.I always give a reason as to why it is necessary to read/ understand the text I am writing about. in other words: Why does it matter for me to write it and for you, the reader, to read it? For example, in the article I am using as an example here, this is the reason I provide to my readers :

This essay discusses the novel’s attempt to represent the 1948 Dakar strike as a clue to learning the absolutely necessary preconditions for successful resistance in the neoliberal regime of high capital. 3

Thus, the essay announces at the outset that there is a two-pronged purpose for this essay: to discuss the chosen text and to draw some particular lessons for real life politics. (Depending upon your particular subfield in English studies, the politics part may not be necessary for you)

Provide an Account of Previous Work on the Text

Then, I provide an account of previous works published about the text and add where I am either building up on previous work or challenging my predecessors’ opinion of the text (Word of advice: be generous in dealing with other people’s work). This is where you will discuss the articles that you had researched during the early stages of your publication plan.

Provide Transitions and Signposting

Do not be afraid of telling your reader as to why you are discussing a certain part of the text, and after discussing a part of the text make sure to provide signposts and clear hints to the reader about where your discussion is headed. Usually at the end of a long paragraph, I add something like this:

Having discussed xx I would now move on to YY, as it is important to zzz.

This kind of signposting is absolutely necessary, as it leads the reader from one part of your argument to the other, thus making the essay more readable and your intent clearer.

Anticipate Counter Arguments/ Criticisms of your Essay and Craft a Built-In Response

As you write your academic articles, try to imagine how someone not familiar with what you are doing or someone invested in a different view of the text would respond to your argument. One of such people could be the reviewer of your academic articles. Where necessary, explain either within the text of your essay or in a footnote that you are aware of an alternative way of looking at the same problem and that you are rather choosing to go in a different direction. You may even provide your reason for this different approach.

Conclusion

Keeping some of these things in your mind, please follow the general writing techniques to finish your first draft. After you have finished your first draft, then you can work to revise it for the soundness of your argument and for style and coherence. It would be great if you could workshop the paper with your mentors and peers. When you think your paper is ready for submission, only then should you consider the next step of submitting the paper. I will discuss the submission and final publication process in Part 4, the final installment of this series on academic publishing in the humanities. (Continue to Part 4)

Please also read the first two parts of this series:

Notes:

- Read my Full article Here ↩

- “Competing Habitus: National Expectations, Metropolitan Market, and Pakistani Writing in English (PWE)”. The Routledge Companion to PakistaniAnglophone Writing. Eds. Aroosa Kanwal and Saiyma Aslam. Routledge 2018: 348-359. ↩

- “Ousmane Sembene’s God’s Bits of Wood: The Anatomy of a Strike and the Ideologeme of Solidarity.” Matatu: Journal for African Culture and Society, Vol. 39 (2011): 423-440. ↩

[…] Home/How to Write and Publish Academic Articles in the Humanities (Part 2) Previous Next […]

[…] Home/How to Write and Publish Academic Articles in the Humanities (Part 4) Previous […]

[…] for publishing, Part Two provides the details about research and writing of a scholarly paper, Part Three deals with writing the first draft, and Part Four informs you about the process of submitting your […]